Celebrating 3 Black Architects Who Shaped Modern Architecture

- PIMM Wix Team

- Feb 3, 2021

- 5 min read

As February is Black History Month, we are sharing the stories of three incredible Black architects and their contributions to the profession. As we all know, talent, creativity, and innovation are universal, but national values and policies have often left Black designers facing unwarranted obstacles. Despite these issues, some of the most remarkable buildings in the world are the work of architects of color who overcame inequality and left marks on the industry and the world. Today, these celebrated structures are testaments to the importance of inclusion, equality, and great design. Keep reading for profiles of some groundbreaking architects and their work! To learn more about Black designers, check out our resources at the bottom of this page!

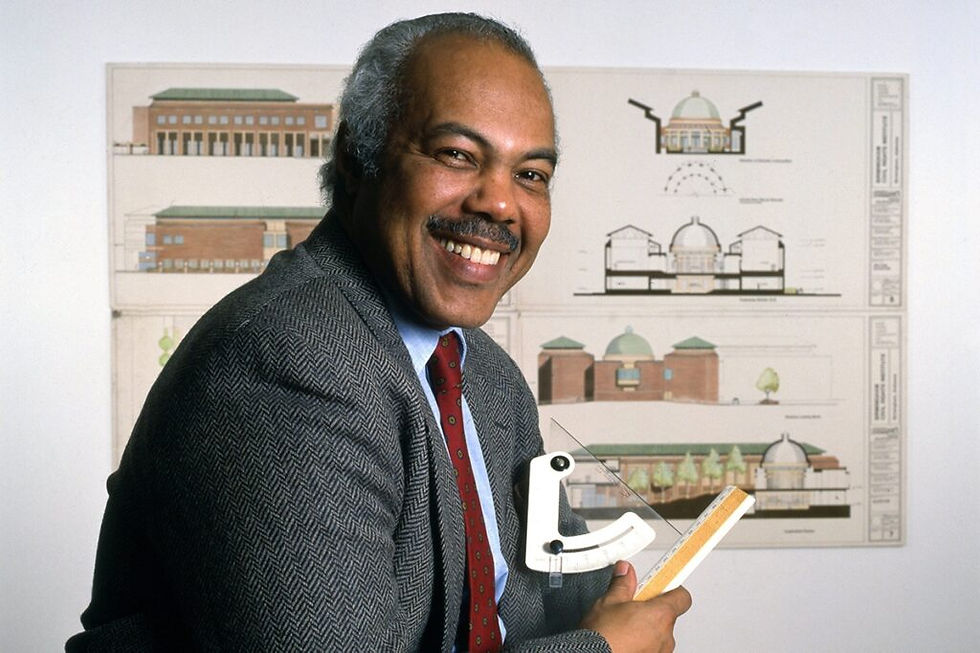

J. Max Bond Jr. (1935-2009)

J. Max Bond Jr. (photo from Harvard University)

Born in Kentucky near the Tuskegee Institute, architect J. Max Bond Jr. was fascinated by the buildings and staircases that made up the campus (the school’s University Chapel is a famously well-designed modern masterpiece, designed by Black architects). When he enrolled in Harvard College, he was faced with cruel treatment by his classmates and professors. After finishing his master’s, he traveled to Ghana, where he worked on government initiatives, including the Bolgatanga Regional Library. Moving to New York in the late 60s, he joined the Civil Rights Movement by founding the Architects Renewal Committee of Harlem, which advocated for the rights of Harlem residents and ensured that new projects would help, not hinder the community. Bond became a leader in design and took on teaching and chairman positions at Columbia and City College. Soon after, he and fellow architect Donald P. Ryder founded Bond Ryder Architects, which went on to design spaces that facilitate social change, such as the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in Alabama, the Harlem Studio Museum, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. After Ryder’s retirement, Bond continued to celebrate Black history by collaborating with David Adjaye on the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, which opened in 2003. Before his passing in 2009, Bond’s firm was selected to design the Memorial and Museum at the World Trade Center, which was completed by his colleagues after his death. His breakthrough involvement, success, and teaching in the field of architecture broke barriers for students of color and created spaces where profound change has been made.

Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (photo from BCRI.org)

Norma Merrick Sklarek (1926-2012)

Norma Merrick Sklarek (photo from PioneeringWomen.org)

As the first licensed female Black architect in the U.S., Norma Sklarek was a pioneer in the architecture field and defied the odds by being accepted to Columbia University’s School of Architecture, where only a handful of women were selected every year. She was one of two women in her 1950 graduating class, and after working at the New York Department of Public Works for four years, made history by passing the architecture examination, and landing a job at prestigious firm Skidmore Owings & Merrill. In 1959, she became the first-ever African American woman member of the American Institute of Architects. Aside from her day job, she taught architecture classes at New York Community College. When she moved to a new firm, Gruen Associates in Los Angeles, she became a registered architect on both coasts. At Gruen, Sklarek worked on projects such as the Pacific Design Center in West Hollywood and the Embassy of the United States in Tokyo as a project manager. Despite her significant role in the design of these buildings, she is unfairly credited as a “manager” and not a designer. In 1980, she went to work for Welton Becket Associates, where she was the director of a new terminal at the Los Angeles International Airport, which was especially important as the L.A. Olympics were counting on the completion of her design. Five years later, she and two fellow female architects founded Siegel, Sklarek, and Diamond, which is one of the largest woman-owned architecture firms of all time. After her retirement, Sklarek was appointed to the California Architects Board and served as chair of the AIA’s National Ethics Council, where she continued to advocate for change until her passing in 2012. Norma Sklarek is known as one of the most admirable and change-making architects in history, achieving several firsts for women and the Black community whose teachings and policymaking live on today.

Pacific Design Center (photo from The-Modernist.org)

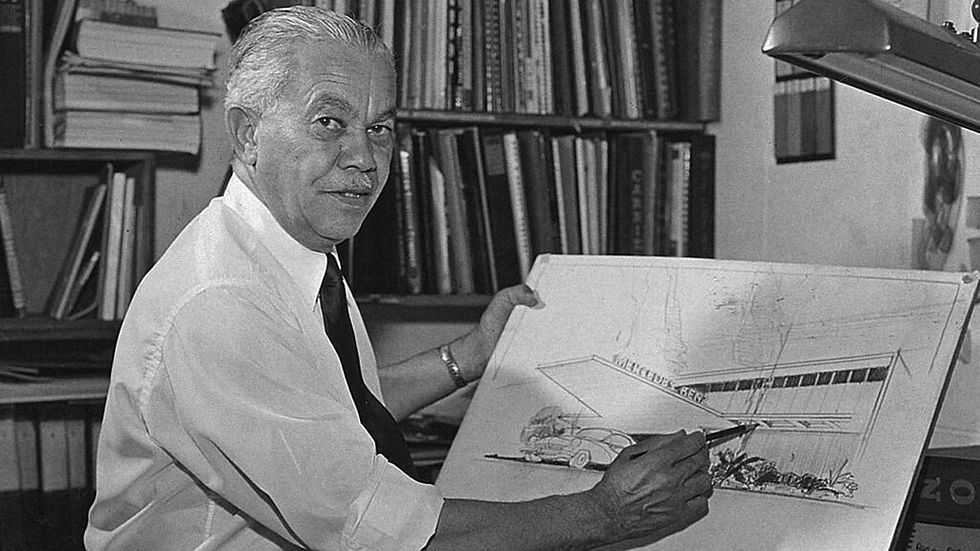

Paul R. Williams (1894-1980)

Paul R. Williams (photo from NPR.org)

As one of the first certified Black architects in U.S. history and one of the most prominent modernists on the West Coast, Los Angeles-born Paul R. Williams grew up as the only African-American person in his school. He was adopted by a white couple after he lost his parents as a child. In college, at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design, he found a love for planning and architecture. For a few years, he spent time as a landscape architect, and after graduating from the University of Southern California, earned his architect certification in 1921. He won an architecture competition soon after and then opened his own office. However, he had trouble gaining popularity due to his race. He learned to draft “upside-down” from across the table when presenting to clients because many of them would not sit next to a Black man. In 1923, Williams became the first Black member of the AIA, and a few years later was awarded the AIA Award of Merit by his peers. Over his long career, Williams designed more than two thousand private homes, many of them for celebrities in the Southern California area. In the 50s, he designed now-iconic homes for Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball, Barbara Stanwyck, and hundreds of other notable figures in the arts, as well as many buildings around Los Angeles, such as an addition to the Beverly Hills Hotel and the Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport (in collaboration with fellow architects Charles Luckman, William Pereira, and Welton Becket). The unfortunate truth was that the land he built many homes on was segregated, and Black people were prevented from purchasing there. During the housing crisis, Williams also worked on charitable projects such as the first post-war low-income housing in Washington, DC, and another in Southeast Los Angeles, creating homes for people who may otherwise not have had them. In 1955, Williams was hired to convert a Woolworths department store in Manhattan into a bank, where he subsequently stored many of his files, drawings, and archives. During unrest in the city years later, the bank was burned, and most of Williams’ files were presumed gone forever. His granddaughter curated the remaining files and they were acquired by the Getty Research Institute and USC School of Architecture. In 2020, forty years after his passing in 1980, USC architecture dean Milton Curry shared that the drawings and plans in the files now serve as important developments in the understanding of twentieth-century modernism.

The La Concha Motel (Bloomberg.com)

Comments